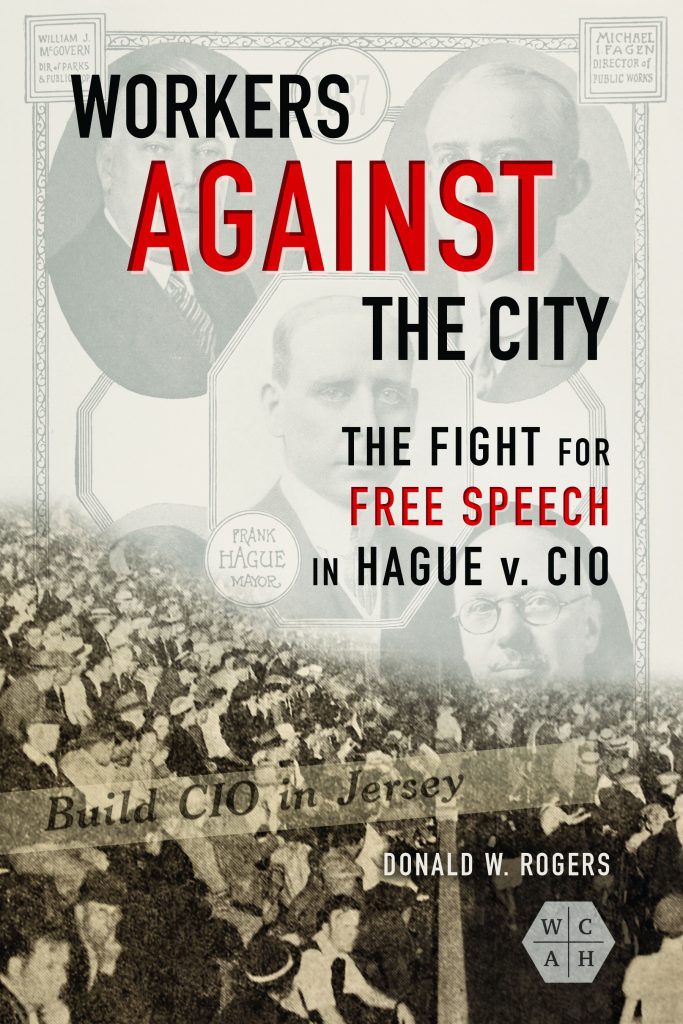

Donald W. Rogers, author of Workers against the City, answers questions about the labor movement, American history, free speech, CIO v. Hague, and civil liberties.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

Free speech and assembly law are central to the practice of American democracy, and I have long had an interest in their development. As I studied and taught twentieth-century civil liberties history, however, it struck me that the 1930s American workers’ upsurge seemed to contribute much more to the advancement of these rights than historical memory credits. My aim in writing this book was to recapture the labor movement’s largely forgotten role in the civil liberties revolution at the end of the New Deal era in the late-1930s. The CIO fight with Jersey City mayor Frank Hague is one compelling and largely misunderstood illustration.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

My doctoral work long ago with Professor Stanley Kutler at University of Wisconsin kindled my interest in civil liberties through American history, thus steering me toward the CIO-versus-Hague story. In the present book Workers against the City, several specific bodies of work influenced my thinking.

First and foremost is David Rabban’s Free Speech in Its Forgotten Years (1997), which documents how American free speech principles were not a fixed heritage, but evolved through the interwar years into their modern form. Second, is the school of work by urban historians like Bruce Stave who revamped my understanding of big-city bosses like Frank Hague not just as corrupt tyrants (as Hague is often portrayed), but as functionally effective leaders in local politics, uncouth and corrupt as some (like Hague) actually were. Third are labor historians beginning with Irving Bernstein decades ago who have chronicled American organized labor’s transformation from a movement predominately of craft unions down to the 1920s to one of industrial unions in the 1930s (a crucial transition that is mostly ignored in tellings of the CIO v. Hague story.) Finally, there is a paring of contrasting literatures on interwar right-versus-left political rhetoric. Robert Justin Goldstein’s edited collection Little “Red Scares” (2014) opened my eyes to the persistent interwar anti-communist rhetoric that Mayor Hague adopted in the Jersey City controversy. Likewise, Christopher Vials’s Haunted by Hitler (2014) taught me about anti-fascist rhetoric that emerged in late-1930s Popular Front. These two rhetorics squared off against each other in the Jersey City case, and they heavily shaped our popular recollection of it down to today.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

My most interesting and unexpected finding in writing Workers against the City involved a central legal issue in the court case ultimately decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in Hague v. CIO. The conventional historical view is that the case was all about affirming First Amendment outdoor speech and assembly rights—which is partly true—but I found while studying Jersey City briefs and subsequent majority and dissenting court opinions that a big threshold constitutional question had to be resolved first—that is, whether federal courts had jurisdiction to intervene in municipal policing of public order. To my surprise, Jersey City briefs reached back to Reconstruction-era Supreme Court decisions like Slaughterhouse and Cruikshank, as well to the 1897 case of Davis v. Massachusetts to defend an increasingly antiquated view of federalism that kept the scrutiny of federal courts out of local municipal affairs.

This discovery taught me how wayward local governments like Jersey City’s had long used constitutional law to shield themselves from federal civil liberties claims before the late-1930s. Workers and their supporters had to break through that barrier to secure protections from the federal Bill of Rights, a major accomplishment that the CIO and its legal allies in the American Civil Liberties Union achieved in the controlling opinion in Hague v. CIO. Even then, the Supreme Court left the rationale for this constitutional change in question with a just a plurality controlling decision and two differing concurrences. This was no slam dunk for civil liberties. The Supreme Court had later to work out details.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel, or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I hope that my book will put aside the prevailing myth that Hague v. CIO simply defeated a would-be local tyrant (Mayor Hague) to affirm long-standing American civil liberties on behalf of workers and their supporters. The case was so much more complicated. For one thing, the prevailing myth uncritically accepts the rhetoric of Hague’s opponents that the mayor was a quasi-fascist, anti-labor authoritarian who opposed all civil liberties. This myth misconstrues urban boss politics and fails fully to investigate how a political machine like Hague’s really worked.

More important, the myth underestimates the role of workers and the CIO in the Hague v. CIO story—why its organizers showed up in Jersey City in the first place, what they hoped to achieve, how a left-leaning coalition of socialists, religious leaders, journalists, and civil libertarians rallied in their support, and how finally their conflict wound up in federal court. It was a long political battle fought out on the streets, then in the press, and ultimately in court. It began as a CIO struggle to organize union locals in Jersey City under the newly enacted National Labor Relations Act but ended up as a fight over civil liberties. The myth leaves out the labor angle.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

In this case, American worker rights advanced, not simply as a product of determined worker agitation, but also because of its confluence with larger historical trends. Historical contingency was important, and worker campaigns did not work out as expected. In the case of Hague v. CIO, the CIO’s fight with Mayor Hague coincided crucially with the “civil liberties revolution” in constitutional law pursued by the ACLU and adopted by receptive federal courts, and with the rise of the Popular Front coalition of New Deal liberals and left-leaning journalists, religious figures, civil libertarians and working-class activists that targeted political figures (like Hague) who resembled European fascists.

These coincidental developments gave the CIO’s organizing campaign a big boost but complicated the results. The CIO (and ACLU) victory in Hague v. CIO certainly facilitated CIO rallies and labor union organizing efforts, leaving CIO unions well-implanted in the municipality by mid-1940s. Ironically, however, the victory did not topple Mayor Hague, who (characteristically) coopted the CIO into his governing coalition. And legally, the Hague decision did little for labor organizing rights to picket, form unions, or bargain collectively per se. In the end, the case was more important as a milestone for out-of-doors protest rights that set the stage for the subsequent civil rights era.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I very much like to read “life-and-times” historical biographies and historical narratives that feature all kinds of people in the Americas and around the world. Maybe discordantly, I listen alternatively to symphonic or jazz music to relax, and occasionally try to replicate either on the keyboard as a perpetual piano beginner. I am not much of a TV watcher or moviegoer but prefer television series and motion pictures that feature historical subjects or themes.