Experimental, strange, and unabashedly feminist, Joanna Russ’s groundbreaking science fiction grew out of a belief that the genre was ideal for expressing radical thought. Her essays and criticism, meanwhile, helped shape the field and still exercise a powerful influence in both SF and feminist literary studies.

Experimental, strange, and unabashedly feminist, Joanna Russ’s groundbreaking science fiction grew out of a belief that the genre was ideal for expressing radical thought. Her essays and criticism, meanwhile, helped shape the field and still exercise a powerful influence in both SF and feminist literary studies.

So if you want to read her work, where do you start? Have no fear reader! Gwyneth Jones, author of Joanna Russ in our Modern Masters of Science Fiction Series has written a handy guide to her work to get you started.

And if you want to learn more about the radical and remarkable Russ, make sure to check out Jones’s book!

———————————————————————————————————–

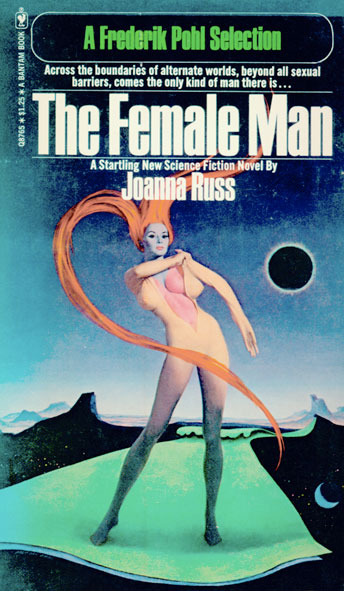

The Female Man

When it dawns on you that some classes and races are exploited, and that prejudice and corruption are rife in your society, all your memories change color. All your hopes for the future vanish and are replaced: it’s as if you’re a new person, in a strange, yet familiar new world. In

The Female Man, Joanna Russ conjures up the story of one woman’s journey towards feminism in a science fiction “multiverse” scenario in which four “Joannas”, from four different realities, meet, squabble, play games, dream dreams, go out to dinner together, fall in love —and seriously contemplate (there’s a dark side) genocide of the human male. Published in 1975, still relevant today; courageously positive and wickedly funny, this book is required reading. “When It Changed,” the original Female Man story, very different from the book, won a Nebula award in 1972.

How To Suppress Women’s Writing

How To Suppress Women’s Writing

“She wrote it but she shouldn’t have . . .” She didn’t really write it, a man did it for her. . . She wrote it but it’s not literature . . . A quirky, scathing and highly entertaining survey of all the ways that works by women —the “cultural minority”— have been dismissed, sneakily devalued, denied, and made to disappear from the official annals of literature, scholarship, science and the arts. Joanna Russ was a scholar and a critic, as well as a science fiction writer and a feminist: in this study you get all the Joannas, dissecting a world of complacent prejudice with style —but not without noting her own unthinking assumptions, about writing by women of color, and how it felt when the scales fell from her eyes. Meticulously argued and very cool: you’ll laugh out loud, but you’ll be gritting your teeth at the same time (if that’s a possible combination), because all of this still happens. Joanna Russ’s only full-length critical work and it’s a dazzler.

(Editor’s Note: This book was recently reissued by our friends at the University of Texas Press)

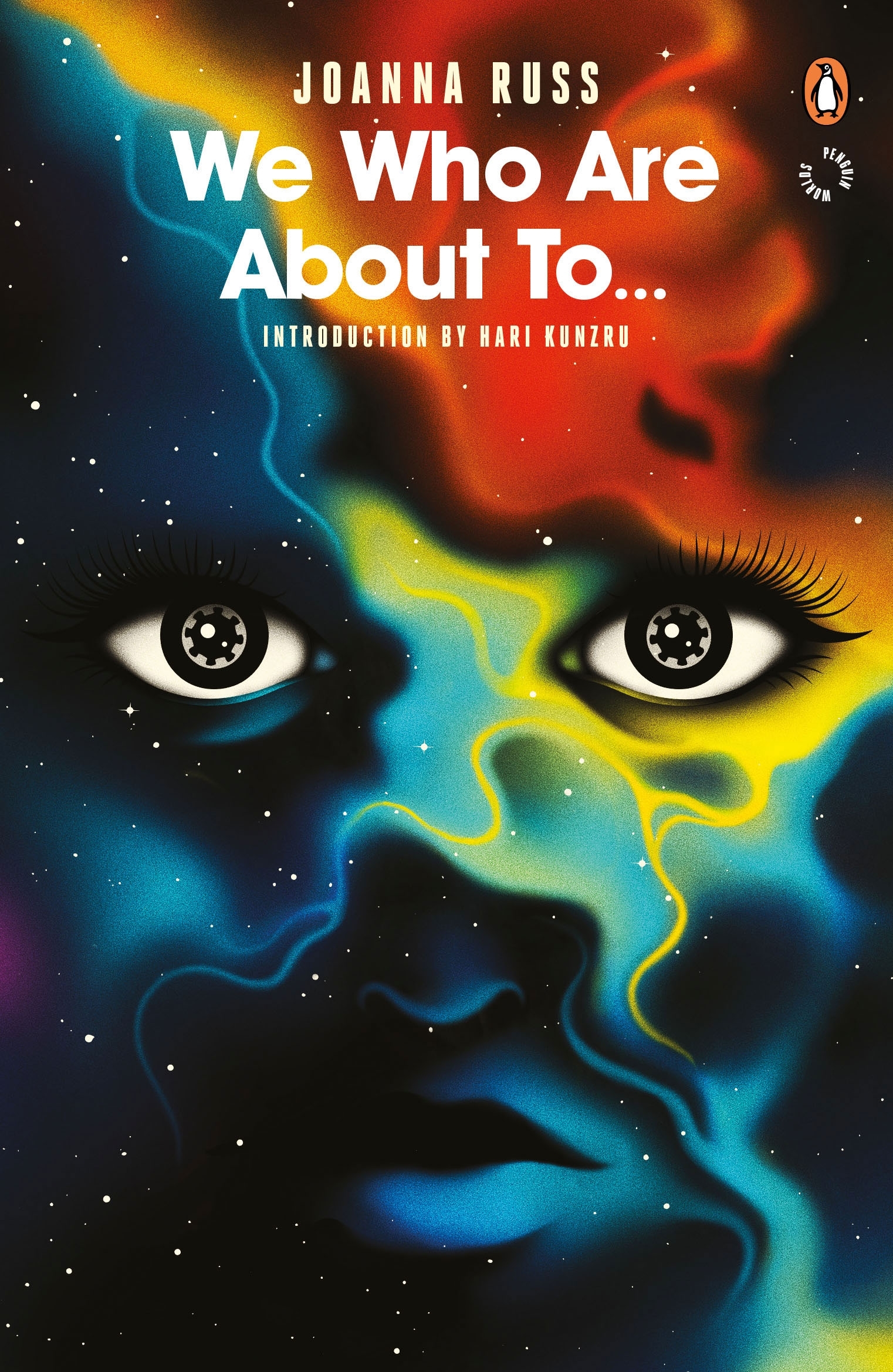

We Who Are About To

We Who Are About To

About to die. We’re all going to die . . . A doomed starship dispatches a handful of clueless tourists to the nearest marginally habitable planet. They’re far, far from any shipping route, with no way to send a distress signal, minimal supplies, no idea if they can find food or water, and not a hope of rescue. Everyone —except for one rebel voice of reason— immediately agrees that the first issue is getting the three childbearing-age women pregnant. But the annoying voice of reason in this sorry crew is not the mild-mannered lady she seems: she’s an outlaw on the run, with a secret stash of desperado tricks . . . Pregnancy by rape, as a means of subduing uppity females, was a hot topic in the sf of the day, but that’s not the only tough theme here, there’s also the arrogance of American expansionism; and then there’s death. It all makes for a gritty and unexpectedly gripping story; with a long, meditative coda that will explain all the rest, if you’re ready to listen.

Extraordinary People

Extraordinary People

A medieval abbess, who is not what she seems, so brave and wise her powers seem supernatural, begins to lose control of her fake persona. Two gender-blind utopians run merry rings around a conflicted guardian of over-stuffed nineteenth century repression. Refugees from the miserable twentieth century struggle with a different utopia’s sweet freedoms, and the Manland vs Womanland War of Mutual Destruction —almost our inescapable future, in The Female Man— gets revisioned with a hopeful twist. Finally, a teasing exchange of letters (about the bestselling Lesbian Gothic Joanna, playing herself, proposes to write), reminds us that the way to a better world always starts with an act of the imagination. These interlinked stories, Joanna’s last major sf project, each of them a delicious, intellectually satisfying treat, are all about understanding that “Utopia” is a process, not a conclusion. “Souls”, the tale of Abbess Radegunde, won a Hugo award in 1983.

Alyx (and other stories)

Alyx (and other stories)

Alyx of Ourdh: a small, tough, not very beautiful woman, fearless in a fight, faithful as a friend, but with a sharp mind and a healthy interest in profit, was born in a story published in 1967 as “The Adventuress”. Further Ourdh-based exploits followed; then a game-changing, but lovingly traditional sf action adventure, Picnic On Paradise, 1968. Arguably the first real female hero in the sf/fantasy genre, so it’s fitting that the last Alyx story, “The Second Inquisition” (1970), is all about how passionately girls like Joanna, growing up in repressive societies, long for female heroes to believe in. In a 1975 interview, Joanna said “writing adventure stories about a woman, in which the woman won” was one of the hardest decisions she ever made . . . Generations of sf/fantasy readers (and writers!) are now eternally grateful that she made the effort. PS: if you like Alyx, seek out Joanna’s story collections, The Zanzibar Cat and The Hidden Side Of The Moon. My favorite, after “When It Changed” is possibly “The Zanzibar Cat” itself.

The Essays

Joanna’s essays on science fiction are stylish, illuminating, and far from stuffily academic. For essential reading try “Towards an Aesthetic of Science Fiction”; or “The Wearing Out Of Genre Materials”; for your guide to sf’s “feminist seventies” there’s “The Image Of Women In Science Fiction”, “Amor Vincit Foeminam. . . The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction,” and “Recent Feminist Utopias”. For the same issues in fiction generally, there’s “What Can A Heroine Do?: Or Why Women Can’t Write” (precursor to How To Suppress Women’s Writing), and for female sexuality running riot, there’s the notorious “Pornography For Women, By Women, With Love” —on the origins of K/S or “Slash” fiction. Many of her essays are available on line, but the collections, Magic Mommas, Trembling Sisters, Puritans and Perverts (1985); To Write Like A Woman (1995), and The Country You Have Never Seen (2007) are well worth seeking out. The Pilgrim award for SF criticism was awarded to Joanna Russ in 1988.

—Gwyneth Jones, author of Joanna Russ