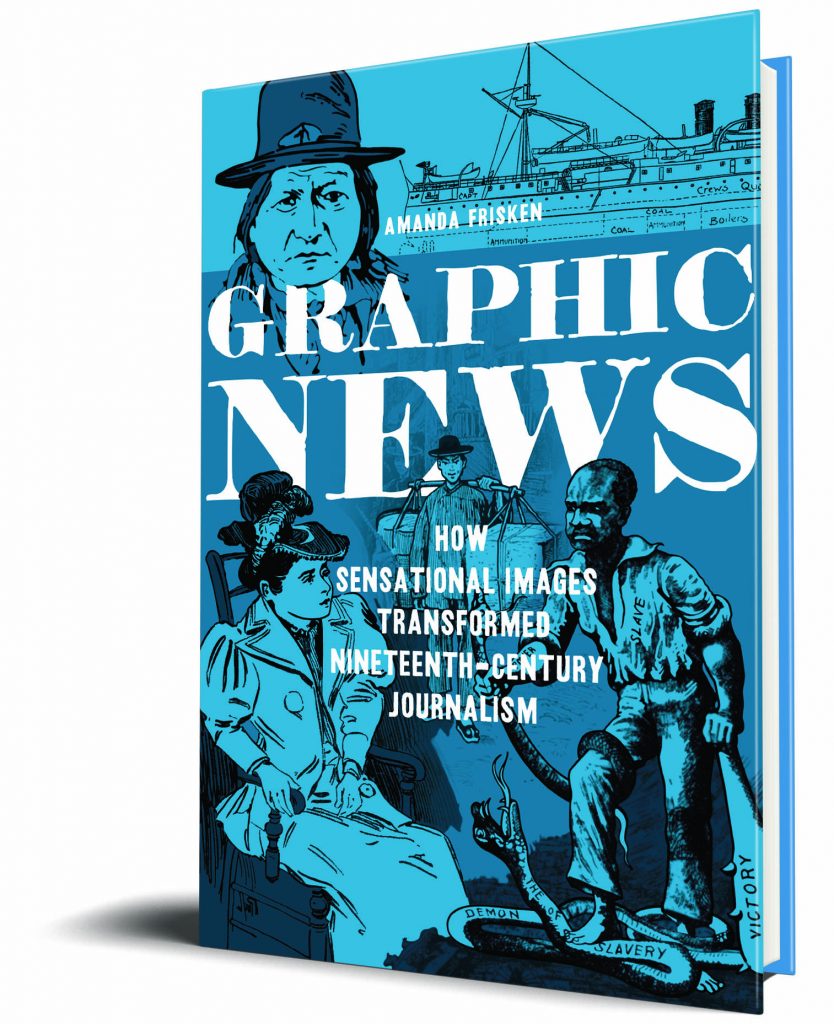

Amanda Frisken, author of Graphic News: How Sensational Images Transformed Nineteenth-Century Journalism answers questions about her inspiration for writing , sensational journalism, and what she hopes readers will take away from her book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

In researching my book about Victoria Woodhull, I uncovered a trove of images from weekly illustrated sporting newspapers that became central to my analysis. I found that illustrated daily and weekly newspapers had a significant impact on political culture in the post-Civil War years. Woodhull was a media event in her own right, but she also used the media – weekly, daily newspapers, and her own press – to influence public opinion. News images, I came to understand, empowered a variety of political players to communicate – and challenge – messages in the public sphere. Major media events of the last few decades of the nineteenth century fueled the rise of sensationalism in weekly and then daily newspapers. And sensational illustrations, intentionally or not, manipulated the way people perceived those events.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

Only a few scholars have explored the cultural meanings of inexpensive, ephemeral news images in any depth. The most important influence on my thinking was probably Joshua Brown, whose Beyond the Lines examines illustrations in weekly newspapers as communicators of complex visual messages. John Coward’s Indians Illustrated,John Tchen’s New York Before Chinatown, and Rebecca Zurier’s Picturing the City were also influential. Several studies of photography have shaped how I think about representations of violence in particular, among them Dora Apel’s and Shawn Michelle Smith’s Lynching Photographs and Ken Gonzales-Day’s Lynching in the West. But there are too many others to name!

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I was fascinated to discover that early, primitive daily news images in the 1880s, which at first I barely noticed, played a vital cultural role. In contrast to weekly illustrations, which conveyed lively narratives, daily news image seemed flat, simplistic, and unimportant, and it was hard to imagine that they had much power to influence anybody’s perception of the news. In researching the chapter on the Ghost Dance, however, I found a tiny image of Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill Cody being used to illustrate a story about the dance. Both men were famous, deeply connected with the celebrity industry as well as the mythology of the Wild West, and the image conveyed meanings to contemporaries that are nearly invisible to readers today. Neither man was central to the Ghost Dance, but when the New York World published their familiar faces it recast the story within an established narrative of European colonization and indigenous resistance. It didn’t matter that the image didn’t match the reality of what was happening in the Plains West – what mattered was that it told a story readers readily understood.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

It’s been axiomatic in media history that sensational journalism became a force in U.S. popular culture only during the lead-up to the Spanish-American war, in 1897-1898. That’s when the term “yellow journalism” emerged as a critique of the new style. Those years were critically important for the rise of sensational journalism – and illustrations did play a key role in that rise. But the cases I explore in Graphic News reveal a much longer and more complicated trajectory. Sensational media tools evolved over decades, from the penny press in the 1830s, through the rise of illustrated weeklies around mid-19th Century, to the explosion of sensational dailies in the 1880s. Decades of experimentation and reaction made sensational illustrations a force to be reckoned with, but they had largely been treated as a curiosity within the history of journalism. Meanwhile, paradigms established in the first illustrated dailies continue to shape how we produce and interpret the news today.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

We’re accustomed to living in an image-saturated environment today, and we flatter ourselves that we’re shrewd enough to notice how visual coverage shapes our understanding of current events. The more I came to see individual images in daily newspapers – portraits, landscapes, re-enactments masquerading as eye-witness documentation – as conveyors of rich narratives all by themselves, the more I appreciated the power of seemingly innocuous images to distort news stories. Sensational news images are not a new phenomenon – they pre-date and established parameters for photojournalism – and they are anything but neutral. News illustrations influenced events in real time as people experienced and then reacted to what they saw. They shaped history, in other words; they still do. My hope is that readers will take away an awareness of persisting strategies developed by editors and artists, in the early years of illustrated daily news production, to sell news media. Ideally, it will alert readers to our continued susceptibility to sensational imagery.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

These days, I read (and re-read) a lot of speculative fiction literature. Two of my favorite go-to authors are Ursula K. LeGuin and Octavia Butler. Apart from the fact that both are brilliant writers and story-tellers, I love the passion, creativity, and playfulness they poured into their art. Today more than ever, I’m just grateful to them for transporting me into other worlds.